Many of us are good at reusing code beyond a certain complexity, but when it comes to writing a “quick” string randomizer, or finding a hash key that corresponds to a maximum value, or traversing a hash structure, etc., we constantly reinvent the wheel. It’s worth doing, to keep computationally fit, but some days we could use that extra half an hour.

Next time you rewrite that algorithm, log it here in the scrapbook, and give the gift of time. Post your favorite solutions to common tasks, elegant algorithms worthy of admiration, or truly frightening code to pique the morbid curiosity of the BioPerl community.

If you’re looking for an answer and don’t see it here, try the HOWTOs, search the BioPerl Archives, or post your question to the listserv (sign up here).

Note: These are donated scraps from various contributors. Please recognize that programming styles may vary widely. If a particular scrap has a bug, feel free to fix the issue by modifying the wiki, but refrain from imposing one’s own programming style upon others, with the singular exception that it doesn’t follow a Best Practice and may lead to problems down the road (we do have Talk pages for those purposes).

A

Analysis_and_Phylogenetics

Finding_all_clades_represented_in_a_tree

- Here is a scrap that will return all clades (i.e., maximal sets of leaf/tip taxa descended from a given single node) in a tree, inspired by a question on Evoldir. Other approaches? – Ed.

# get $tree somehow, e.g. from $treeio->next_tree (see Bio::TreeIO)

my @nodes = $tree->get_nodes;

my %clades;

foreach my $n (@nodes) {

my @desc = $n->get_all_Descendents;

if ($n->is_Leaf) {

# degenerate clades...

$clades{$n->id}++;

}

else {

my @lvs = grep { $_->is_Leaf } @desc;

$clades{ join(',',sort map {$_->id} @lvs) }++;

}

} return keys %clades;

- Another approach, using Bio::Tree::Compatible of G. Valiente. If the internal intervening nodes are labeled (have a non-empty

id()property), they will also appear in the output.

use Bio::TreeIO;

use Bio::Tree::Compatible;

my $tio = Bio::TreeIO->new(-format=>'newick',-file => $file);

while (my $t = $tio->next_tree) {

map {

print "(",join(',',@{$_}),")\n"

} values %{Bio::Tree::Compatible::cluster_representation( $t ) };

}

File content:

(((A:5,B:5):2,(C:4,D:4):1):3,E:10);

(((A:5,B:5)x:2,(C:4,D:4)y:1)z:3,E:10)r;

–MAJ

Poor_man’s_bootstrap

(see the bioperl-l thread here)

- As Russell often says, sometimes Perl can do the job by itself. However, if you want to bootstrap sequences from an alignment, have a look at Bio::Align::Utilities… –Ed.

Shalabh Sharma asks

I was just wondering, is there any module is bioperl that does subsampling?

from Mark Jensen:

- To subsample lines from a file with replacement:

If you trust rand()…

# open your file into $my_infile, then

@lines = <$my_infile>;

my $num_samps = 10;

my $sample_size_pc = 0.25;

my @samples;

for (1..$num_samps) {

push @samples = [map { int( @lines * rand ) } ( 0..int($sample_size_pc * @lines) ) ];

}

# now, do something, fr'instance

my @sample_pc;

foreach (@samples) {

my $pct=0;

foreach my $line (@lines[ @$_ ]) {

@a = split(/\s+/,$line);

$pct += $a[2];

}

$pct /= @$_;

push @sample_pc, $pct;

}

# etc...

Site_entropy_in_an_alignment

(see bioperl-l discussion here).

Claudio Sampaio asks

How to get the entropy of each nucleotide of an alignment?

from Mark Jensen:

If you have a Bio::SimpleAlign object prepared

$alnio = new Bio::AlignIO(-format=>'fasta', -file=>'your.fas');

$aln = $alnio->next_aln;

try the following function, as

$entropies = entropy_by_column( $aln )

=head2 entropy_by_column

Title : entropy_by_column

Usage : entropy_by_column( $aln )

Function: returns the Shannon entropy for each column in an alignment

Example :

Returns : hashref of the form { $column_number => $entropy, ... }

Args : a Bio::SimpleAlign object

=cut

sub entropy_by_column {

my ($aln) = @_;

my (%ent);

foreach my $col (1..$aln->length) {

my %res;

foreach my $seq ($aln->each_seq) {

my $loc = $seq->location_from_column($col);

next if (!defined($loc) || $loc->location_type eq 'IN-BETWEEN');

$res{$seq->subseq($loc)}++;

}

$ent{$col} = entropy(values %res);

}

return [%ent];

}

=head2 entropy

Title : entropy

Usage : entropy( @numbers )

Function: returns the Shannon entropy of an array of numbers,

each number represents the count of a unique category

in a collection of items

Example : entropy ( 1, 1, 1 ) # returns 1.09861228866811 = log(1/3)

Returns : Shannon entropy or undef if entropy undefined;

Args : an array

=cut

use List::Util qw(sum);

sub entropy {

@a = grep {$_} @_;

return undef unless grep {$_>0} @a;

return undef if grep {$_<0} @a;

my $t = sum(@a);

$_ /= $t foreach @a;

return sum(map { -$_*log($_) } grep {$_} @a);

}

Site_frequencies_in_an_alignment

To get an array of hashes of hashes containing the frequencies of each residue at each site of an alignment:

$freqs = freqs_by_column($aln);

=head2 freqs_by_column

Title : freqs_by_column

Usage : freqs_by_column( $aln )

Function: returns the freqs for each column in an alignment

Example :

Returns : hashref of the form { $column_number => {'A'=>$afreq,...}, ... }

Args : a Bio::SimpleAlign object

=cut

sub freqs_by_column {

my ($aln) = @_;

my (%freqs);

foreach my $col (1..$aln->length) {

my %res;

foreach my $seq ($aln->each_seq) {

my $loc = $seq->location_from_column($col);

next if (!defined($loc) || $loc->location_type eq 'IN-BETWEEN');

$res{$seq->subseq($loc)}++;

}

$freqs{$col} = freqs(\%res);

}

return { %freqs};

}

=head2 freqs

Title : freqs

Usage : freqs( \%ntct )

Function: returns the site frequencies of nts in an aligment

Returns : hashref of freqs: { A => 0.5, G => 0.5 }

Args : hashref of nt counts { A => 100, G => 100 }

=cut

sub freqs {

my $ntct = shift;

my $t = eval join('+', values %$ntct);

my @a = qw( A T G C );

my @f = map {$_ /= $t} @{$ntct}{@a};

$t = eval join('+', @f);

map { $_ /= $t } @f;

my %ret;

@ret{@a} = @f;

return { %ret}

}

but don’t expect to set any speed records.

D

Databasing

Accessing_GB_flat_files_by_GI

(see bioperl-l thread here.)

Jarod Pardon asks:

I have some sequence databases such as RefSeq in flat GenPept/GenBank format. There is a list of GI numbers and I want to extract the sequence from the database according to the GI number.

Mark Jensen replies:

Bio::DB::Flat is nicely generalized to allow different ‘namespaces’ for the different identifiers used on different sequences. You can choose the type of identifier you want (gi, in your case) by using get_Seq_by_acc() as follows (this actually works on my machine):

$db = Bio::DB::Flat->new(-directory => "$ENV{HOME}/scratch",

-dbname => 'mydb',

-format => 'genbank',

-index => 'bdb',

-write_flag => 1);

$db->build_index("$ENV{HOME}/scratch/plastid1.rna.gbff");

$seq = $db->get_Seq_by_acc('GI' => 71025988);

If you want to get by accession number, use get_Seq_by_acc('ACC' => $accno), etc.

ACE_file_Q&D_filtering

(see the thread on bioperl-l)

from Abhi Pratap:

I am looking for some code to parse the ACE file format. I have big ACE files which I would like to trim based on the user defined Contig name and specific region and write out the output to another fresh ACE file.

Russell Smithies responds:

Here’s how I’ve been doing it:

my $infile = "454Contigs.ace";

my $parser = new Bio::Assembly::IO(-file => $infile ,-format => "ace") or die $!;

my $assembly = $parser->next_assembly;

# to work with a named contig

my @wanted_id = ("Contig100");

my ($contig) = $assembly->select_contigs(@wanted_id) or die $!;

#get the consensus

my $consensus = $contig->get_consensus_sequence();

#get the consensus qualities

my @quality_values = @{$contig->get_consensus_quality()->qual()};

Eds. note: ACE file writing is another matter–but with solutions around the corner. See the rest of the discussion.

BioSQL

BioSQL is a part of the OBDA standard and was developed as a common sequence database schema for the different language projects within the Open Bioinformatics Foundation.

The BioPerl client implementation is bioperl-db. It provides an Object-Relational Mapping (ORM) for various BioPerl objects, such as Bio::SeqI. Here is a simple example:

#!/usr/bin/perl

use strict;

use Bio::Seq;

use Bio::DB::BioDB;

# create a database adaptor, actual parameters depend on your local database installation, here postgresql

my $dbadp = Bio::DB::BioDB->new(-database => 'biosql',

-user => 'biosql',

-dbname => 'biosql',

-host => 'localhost',

-driver => 'Pg');

my $adp = $dbadp->get_object_adaptor("Bio::SeqI");

my $acc = "XP_000001"; # just a dummy

my $seq = Bio::Seq->new(-accession_number => $acc,

-namespace => 'swissprot',

-version => $ver);

my $dbseq = $adp->find_by_unique_key($seq);

my $feat = Bio::SeqFeature::Generic->new(-primary_tag => $primary_tag,

-strand => 1,

-start => 100,

-end => 10000,

-source_tag => 'blat');

$dbseq->add_SeqFeature($feat);

$dbseq->store;

Species_names_from_accession_numbers

- A Bio::DB::EUtilities scrap, showing how you can profitably combine “elink” and “esummary” –Ed.

Bhakti Dwivedi wonders:

Does anyone know how to retrieve the “Source” or the “Species name” given the accession number?

The following scrap (with portions suspiciously reminiscent of the EUtilities HOWTO) demonstrates how you might do this:

use Bio::DB::EUtilities;

my (%taxa, @taxa);

my (%names, %idmap);

# these are protein ids; nuc ids will work by changing -dbfrom => 'nucleotide',

# (probably)

my @ids = qw(1621261 89318838 68536103 20807972 730439);

my $factory = Bio::DB::EUtilities->new(-eutil =>

'elink',

-db => 'taxonomy',

-dbfrom => 'protein',

-correspondence => 1,

-id => \@ids);

# iterate through the LinkSet objects

while (my $ds = $factory->next_LinkSet) {

$taxa{($ds->get_submitted_ids)[0]} = ($ds->get_ids)[0]

}

@taxa = @taxa{@ids};

$factory = Bio::DB::EUtilities->new(-eutil => 'esummary',

-db => 'taxonomy',

-id => \@taxa );

while (local $_ = $factory->next_DocSum) {

$names{($_->get_contents_by_name('TaxId'))[0]} =

($_->get_contents_by_name('ScientificName'))[0];

}

foreach (@ids) {

$idmap{$_} = $names{$taxa{$_}};

}

# %idmap is

# 1621261 => 'Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv'

# 20807972 => 'Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis MB4'

# 68536103 => 'Corynebacterium jeikeium K411'

# 730439 => 'Bacillus caldolyticus'

# 89318838 => undef (this record has been removed from the db)

1;

–maj

F

Fetching

HOWTO:EUtilities_Cookbook

HOWTO:Getting_Genomic_Sequences

See HOWTO:Getting_Genomic_Sequences

Human_genomic_coordinates_and_sequence

- Note that the first script doesn’t get it quite right, but it stays within BioPerl. Replace

get_genomic_sequence()with the second version to get the exact solution. This requires[Bio::EnsEMBL](https://metacpan.org/pod/Bio::EnsEMBL)tools; see link below. –Ed.

Emanuele Osimo, after working hard with HOWTO Getting Genomic Sequences, says:

The script works fine, but gives me the wrong coordinates…there are two different sets of coordinates. The first is called “NC_000001.10 Genome Reference Consortium Human Build 37 (GRCh37), Primary_Assembly”, and is the one I need, and the second one is called just “NT_004610.19” and it’s the one that the script prints. Do you know how to make the script print the “right” coordinates (at least,the ones I need)?

After solving this, the follow-up question:

Could you please tell me how to use the RefSeq coordinates in another script that fetches the sequence, for instance?

Below is a script that fetches chromosomal coordinates based on a geneID, and uses those to obtain chromosomal nucleotide sequence. It’s hacky, but (sort of) works today (23:12, 23 July 2009 (UTC)).

use strict;

use Bio::DB::EntrezGene;

use Bio::WebAgent;

use Bio::DB::EUtilities;

use Bio::DB::GenBank;

use Bio::SeqIO;

use Bio::Root::IO;

my $ua = Bio::WebAgent->new();

my $db = new Bio::DB::EntrezGene;

my ($chr,$start, $end, $info);

my @geneids = (842, 843, 844);

for my $geneid ( @geneids ) {

($chr,$start, $end, $info) = genome_coords($geneid, $db, $ua);

my $seq_obj = get_genomic_sequence($chr, $start, $end);

print $seq_obj->seq; # or whatever you want

}

sub genome_coords {

my ($id, $db, $ua) = @_;

my $seq = $db->get_Seq_by_id($id);

my $ac = $seq->annotation;

for my $ann ($ac->get_Annotations('dblink')) {

if ($ann->database eq 'UCSC')

{

my $resp = $ua->get($ann->url);

my ($chr, $start, $end, $info) =

$resp->content =~ m{position=chr([0-9]+):([0-9]+)-([0-9]+)

\&.*\&refGene.*?\">(.*?)</A>}gx;

return unless $chr;

return ($chr, $start, $end, $info);

}

}

return; # parse error, no UCSC link on page

}

sub get_genomic_sequence {

my ($chr, $start, $end) = @_;

my $fetcher = Bio::DB::EUtilities->new(-eutil => 'efetch',

-db => 'nucleotide',

-rettype => 'gb');

my $strand = $start > $end ? 2 : 1;

my $acc = sprintf("NC_%06d", $chr); # standard locations for current hum genome build

# NC_000022 is X, NC_000023 is Y. NCC_1701 is the Enterprise.

$fetcher->set_parameters(-id => $acc,

-seq_start => $start,

-seq_stop => $end,

-strand => $strand);

my $seq = $fetcher->get_Response->content;

# there must be a better way than below, but oh well...

if ($seq) {

my ($fh, $fn) = Bio::Root::IO::tempfile();

print $fh $seq;

close $fh;

my $seqio = Bio::SeqIO->new(-file=>$fn, -format=>'genbank');

return $seqio->next_seq;

}

return;

}

–Ed.

Emanuele submits:

I discovered that the coupling of the two subs that Mark posted doesn’t get the right results. I think this is because one gets the coordinates with RefSeq build 36.3, the other with build 37. I found that coupling the first sub, genome_coords, with the Bio::EnsEMBL::Registry fetch by region API is a lot better, and it actually generates sequences that contain the genes.

Here is a modified get_genomic_sequence, based on EO’s script. This requires Bio::EnsEMBL::*; get it here, and see the core API docs here:

use Bio::EnsEMBL::Slice;

use Bio::EnsEMBL::Registry;

# returns a Bio::EnsEMBL::Gene

sub get_genomic_sequence {

my ($chr, $start, $end) = @_;

my $registry = 'Bio::EnsEMBL::Registry';

$registry->load_registry_from_db(

-host => 'ensembldb.ensembl.org',

-user => 'anonymous'

);

my $slice_adaptor = $registry->get_adaptor( 'Human', 'Core', 'Slice' );

my $slice = $slice_adaptor->fetch_by_region( 'chromosome', $chr, $start, $end );

return $slice;

}

G

Graphics

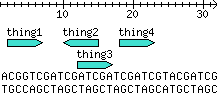

Adding_a_DNA_track

The hack

I thought this was helpful, since the only DNA track example documentation I could find was in the POD of bioperl-live (not on search.cpan.org yet). Thoughts? –Jhannah 02:48, 13 May 2008 (UTC)

The script

use strict;

use Bio::Graphics;

use Bio::SeqFeature::Generic;

# -------------------------------------

# Configure these... ( name start end )

my @stuff = qw(

thing1 2 6

thing2 14 10

thing3 12 16

thing4 18 22

);

my $seq = 'ACGGTCGATCGATCGATCGATCGTACGATCG';

# --------------------------------------

my $panel = Bio::Graphics::Panel->new(

-length => length($seq), # bp

-width => length($seq) * 7, # pixels

);

# Add the arrow at the top.

my $full_length = Bio::SeqFeature::Generic->new(

-start => 1,

-end => length($seq),

);

$panel->add_track($full_length,

-glyph => 'arrow',

-tick => 2,

-fgcolor => 'black',

-northeast => 1,

);

# Data track...

my $track = $panel->add_track(

-glyph => 'generic',

-stranded => 1,

-label => 1,

);

# Add each feature to the data track.

while (@stuff) {

my ($name, $start, $end) = splice @stuff, 0, 3;

my $feature = Bio::SeqFeature::Generic->new(

-strand => $start < $end ? 1 : -1,

-display_name => $name,

-start => $start,

-end => $end,

);

$track->add_feature($feature);

}

# Add the DNA track to the bottom.

my $dna = Bio::PrimarySeq->new( -seq => $seq );

my $feature = Bio::SeqFeature::Generic->new( -start => 1, -end => length($seq) );

$feature->attach_seq($dna);

$panel->add_track( $feature, -glyph => 'dna' );

# Send to a .png file.

print $panel->png;

Output:

Drawing_with_multiple_glyphs_in_a_single_track

(see the bioperl-l thread starting here)

- Don’t neglect your anonymous functions. –Ed.

Matthew Betts asks:

Has any one tried to draw secondary structure with Bio::Graphics, i.e. two different types of glyph with different colours on the same track?

Scott Cain replies:

If you want to put more than one glyph and/or more than one color in a track, it is fairly easy. You just need to provide a callback for each option when you create the track, like this:

$panel->add_track($features_array_ref,

-glyph => sub { #code to set the glyph according the attributes of the feature },

-bgcolor => sub { #code to set the color },

-fgcolor => 'black',

...etc...

);

For more information, see the Graphics HOWTO

Matthew implements:

$panel->add_track(

'-bgcolor' => sub {

my($feature) = @_;

$feature->display_name eq 'strand' ? 'cyan' : 'magenta';

},

'-strand_arrow' => sub {

my($feature) = @_;

$feature->display_name eq 'strand' ? 1 : 0;

},

);

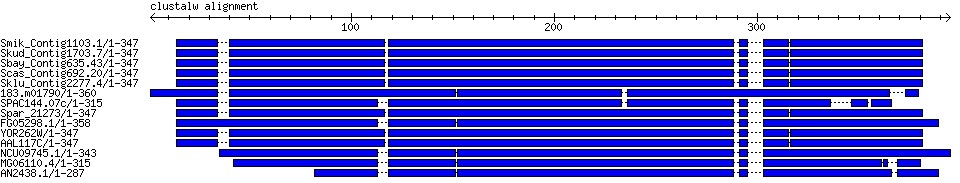

Simple_graphical_alignment_overview

The hack

From Christopher Fields

A simple alignment overview plotter (requires GD::SVG, Bio::Graphics, and bioperl-live). This takes alignment data and prints out the sequences in blocks with dotted lines indicating gaps.

To change to PNG output, delete/comment the -image_class parameter passed to the Bio::Graphics::Panel instance and change the last line to print $panel->png.

The script

#!/usr/bin/perl

use strict;

use Bio::Graphics;

use Bio::AlignIO;

use Bio::SeqFeature::Generic;

my $file = shift or die "Usage: render_alignment.pl <clustalw file> ";

my $aio = Bio::AlignIO->new(-file => $file,

-format => 'clustalw') or die "parse failed";

my $aln = $aio->next_aln() or die "no alignment";

my $panel = Bio::Graphics::Panel->new(

-image_class => 'SVG',

-length => $aln->length,

-width => 800,

-pad_left => 150,

-pad_right => 10,

);

my $full_length = Bio::SeqFeature::Generic->new(

-start => 1,

-end => $aln->length,

-display_name => 'clustalw alignment',

);

$panel->add_track($full_length,

-glyph => 'arrow',

-tick => 2,

-fgcolor => 'black',

-double => 1,

-label => 1,

);

my $track = $panel->add_track(

-glyph => 'segments',

-label => 1,

-connector => 'dashed',

-bgcolor => 'blue',

-label_position => 'alignment_left',

-font2color => 'red'

);

for my $seqobj ($aln->each_seq) {

my $seq = $seqobj->seq;

my @seqs;

# get alignment positions for seqs

my $feature = Bio::SeqFeature::Generic->new(

-display_name => $seqobj->get_nse,

);

while ($seq =~ m{([^-]+)}g) {

# zero-based coords, must adjust accordingly

$feature->add_sub_SeqFeature(

Bio::SeqFeature::Generic->new(-start => pos($seq)-length($1)+1,

-end => pos($seq),

-sequence => $1), 'EXPAND');

}

$track->add_feature($feature);

}

print $panel->svg;

Fig. 1: Graphical alignment output

H

Hugeness_Issues

Counting_k-mers_in_large_sets_of_large_sequences

(This is the fruit of two scraps, Getting all k-mer combinations of residues and Sharing large arrays among multiple threads)

Marco Blanchette contributes the following scripts. Script 1 (countKmer.pl) processes a (possibly very) large sequence file using multiple threads, to return the frequency distribution of k-mers of arbitrary length k. Script 2 (sampleAndCountKmer.pl) does the same thing, if desired, or will randomly sample the sequences (with or without replacement) to return an empirical frequency distribution of k-mers. The user can also specify whether to count just presence/absence of a k-mer in a sequence, or to return a complete frequency distribution.

#!/usr/local/bin/perl

# countKmer.pl take a series of fasta files and count all the occurrence of all the

# possible kmers in each files. It's a multi-threaded scripts that treat multiple files

# asynchronously

use strict;

use warnings;

use Getopt::Std;

use threads;

use Thread::Queue;

our ($opt_k,$opt_m,$opt_p);

our $SEP="\t";

MAIN:{

init();

my $q = Thread::Queue->new;

$q->enqueue(@ARGV);

my $num_workers = @ARGV < $opt_p ? @ARGV : $opt_p; # no need to be wasteful :)

for (1 .. $num_workers) {

threads->new(\&worker, $q);

}

$_->join for threads->list;

}

sub worker {

my $queue = shift;

while (my $filename = $queue->dequeue_nb) {

processFile($filename);

}

return(0);

}

sub processFile {

my $file = shift;

#generate all possible word for a k-mer (define at run time by $opt_k)

print STDERR "Generating all the possible sequences $opt_k long\n";

my $kmer_p = kmer_generator($opt_k);

print STDERR "Counting the number of $opt_k nt long kmers in $file\n";

loadSeq($file,$kmer_p);

##print out the hits

printHits($kmer_p,$file);

}

sub loadSeq {

my $file = shift;

my $kmer_p = shift;

open FH, "$file" || die "Can't open file $file\n";

my $f=0;

my $seq;

while(<FH>){

if(/^>/){

countKmer(\$seq,$kmer_p) if $seq;

$seq='';

$f=1;

}elsif($f==1){

chomp;

next if "";

$seq = join("",$seq,$_);

}

}

countKmer(\$seq,$kmer_p) if $seq; # do not forget the last sequence

close FH;

return(0);

}

sub countKmer {

my $seq_p = shift;

my $kmer_p = shift;

my $k = $opt_k;

my %beenThere;

for (my $i=0;$i <= length(${$seq_p})-$k;$i++){

my $w = substr(${$seq_p},$i,$k);

unless ($opt_m){

#Count only one occurrence of a kmer per sequence

$kmer_p->{$w}++ if !exists $beenThere{$w} && exists $kmer_p->{$w};

$beenThere{$w}=1;

}else{

#Count all instances of a kmer per sequence

$kmer_p->{$w}++ if exists $kmer_p->{$w};

}

}

return(0);

}

sub printHits {

my $kmer_p=shift;

my $file = shift;

##print out the hits

my ($dir,$pre,$suf) = ($file =~ /(^.+\/|^)(.+)\.(.+$)/);

open OUT, ">$pre.hits" || die "Can't create file $pre.hits\n";

print OUT join($SEP, $_, $kmer_p->{$_}), "\n" for sort keys %{$kmer_p};

close OUT;

return(0);

}

sub kmer_generator {

my $k = shift;

my $kmer_p;

my @bases = ('A','C','G','T');

my @words = @bases;

for (my $i=1;$i<$k;$i++){

my @newwords;

foreach my $w (@words){

foreach my $b (@bases){

push (@newwords,$w.$b);

}

}

undef @words;

@words = @newwords;

}

map{ $kmer_p->{$_}=0} @words;

return($kmer_p);

}

sub init {

getopts("p:k:m");

unless (@ARGV){

print("\nUsage: countKmer.pl [-k 6 -p 4 -m] sequence_1.fa [sequence_2.fa ...]\n",

"\tFor each possible words in the kmer of lenght -k,\n",

"\tcount the number of time they are found in the fasta sequence file\n",

"\t-k\tsize of the kmer to analyze. Default 6\n",

"\t-m\twill count all possible kmer per sequences.\n",

"\t\tDefault: only one kmer is counted per sequence entries\n",

"\t-p\tThe number of jobs to process simultaneoulsy. Normally, the number of available processors\n",

"\t\tDefault: 4\n",

"\n",

);

exit(1)

}

$opt_k=6 unless $opt_k;

$opt_p=4 unless $opt_p;

return(0);

}

Script 2 (sampleAndCountKmer.pl)

#!/usr/local/bin/perl

# sampleAndCountKmer.pl is a bootstrapping procedure that sample a list of sequences a

# certain number of time and return the count of each kmer in each sampling. Again this

# is a mutli-threaded scripts that will count multiple samples asynchronously

use strict;

use warnings;

use Getopt::Std;

use threads;

use threads::shared;

use Thread::Queue;

our ($opt_f,$opt_k,$opt_m,$opt_p,$opt_s,$opt_n,$opt_w,$opt_v);

our $SEP="\t";

MAIN:{

init();

my $file = $opt_f;

my $seq_p = loadSeq($opt_f);

#create the final result hash with shared arrays at each kmers.

my $res = &share({});

$res = kmer_generator($opt_k);

$res->{$_} = &share([]) for keys %{$res};

my $q = Thread::Queue->new;

$q->enqueue(1..$opt_n);

my $num_workers = $opt_p; # no need to be wasteful :)

for (1 .. $num_workers) {

threads->new(\&worker, $q, $seq_p, $res, $_);

}

for (threads->list){

$_->join;

}

##Now, need to deconvolute the arrays containing all the counts for all kmers

##and spit out a table of count for all the samples

print(join ("$SEP",$_,@{$res->{$_}}),"\n") for keys %$res;

print STDERR "all done!\n" if $opt_v;

}

sub worker {

my $queue = shift;

my $seq_p = shift;

my $res = shift;

my $t_id = shift;

while (my $q_id = $queue->dequeue_nb) {

processSeq($q_id,$seq_p,$res);

}

return(0);

}

sub processSeq {

my $q_id = shift;

my $seq_p = shift;

my $res = shift;

#generate all possible word for a k-mer (define at run time by $opt_k)

print STDERR "Generating all the posible sequences $opt_k nucleotid long kmer for sample $q_id\n" if $opt_v;

my $kmer_p = kmer_generator($opt_k);

#randomly sample the sequences

my $sample = sampleSeq($seq_p,$q_id);

#counting the number of kmers in the sample seq

print STDERR "Counting the number of $opt_k nt long kmers in the $q_id sample\n" if $opt_v;

map{ countKmer($_,$kmer_p) } @{$sample};

#put the hits in the final result kmer;

map { push @{$res->{$_}}, $kmer_p->{$_} } keys %{$res};

return(0);

}

sub sampleSeq {

my $seq_p = shift;

my $q_id = shift;

my $sample_size = $opt_s;

#create a list of $sample_size items of randomly selected position in @seqs

my @lines;

unless ($opt_w){

##Sampling with replacement

while (scalar(@lines) < $sample_size){

push @lines, int(rand(@{$seq_p}));

}

}else{

##Sampling without replacement

my %lines;

while (scalar(keys %lines) < $sample_size){

$lines{int(rand(@{$seq_p}))}='';

}

@lines = keys %lines;

}

print STDERR "Sampling $sample_size items for the sample $q_id\n" if $opt_v;

my @sample = map { $seq_p->[$_] } @lines;

return(\@sample);

}

sub loadSeq {

my $file = shift;

my $seq_p;

open FH, "$file" || die "Can't open file $file\n";

my $f=0;

my $seq;

while(<FH>){

if(/^>/){

push @{$seq_p}, $seq if $seq;

$seq='';

$f=1;

}elsif($f==1){

chomp;

next if "";

$seq = join("",$seq,$_);

}

}

close FH;

return($seq_p);

}

sub countKmer {

my $seq = shift;

my $kmer_p = shift;

my $k = $opt_k;

my %beenThere;

for (my $i=0;$i <= length($seq)-$k;$i++){

my $w = substr($seq,$i,$k);

unless ($opt_m){

#Count only one occurrence of the kmer per sequence

$kmer_p->{$w}++ if !exists $beenThere{$w} && exists $kmer_p->{$w};

$beenThere{$w}=1;

}else{

#Count all instances of each kmers in a sequence

$kmer_p->{$w}++ if exists $kmer_p->{$w};

}

}

return(0);

}

sub printHits {

my $kmer_p=shift;

my $file = shift;

##print out the hits

my ($dir,$pre,$suf) = ($file =~ /(^.+\/|^)(.+)\.(.+$)/);

open OUT, ">$pre.hits" || die "Can't create file $pre.hits\n";

print OUT join($SEP, $_, $kmer_p->{$_}), "\n" for keys %{$kmer_p};

close OUT;

return(0);

}

sub kmer_generator {

my $k = shift;

my $q_id=shift;

my $kmer_p;

my @bases = ('A','C','G','T');

my @words = @bases;

for (my $i=1;$i<$k;$i++){

my @newwords;

foreach my $w (@words){

foreach my $b (@bases){

push (@newwords,$w.$b);

}

}

undef @words;

@words = @newwords;

}

map{ $kmer_p->{$_}=0} @words;

return($kmer_p);

}

sub init {

getopts("f:p:k:s:n:mwv");

unless ($opt_f){

print("\nUsage:tsampleAndCountKmer.pl [-k 6 -p 4 -s 100000 -n 1000 -m -w] -f sequence.fa\n",

"\twill return a table of counts for each k-mers of length -k\n",

"\t-f\tFasta database. Required\n",

"\t-k\tsize of the k-mer to analyze. Default 6\n",

"\t-m\twill count all possible k-mer per sequence.\n",

"\t\tDefault: only one k-mer is counted per sequence entries\n",

"\t-s number of sequences to sample. Default: 100,000 sequences\n",

"\t-n number of times to repeat the sampling/counting procedures. Default: 1000 times\n",

"\t-w Sample without replacment: Default: with replacement\n",

"\t-p\tThe number of jobs to process simultaneoulsy. Normally, the number of available processors\n",

"\t\tDefault: 4\n",

"\t-v Run in verbrose mode. Spits out a lot of infomation. Default: quiet\n",

"\n",

);

exit(1)

}

$opt_k=6 unless $opt_k;

$opt_p=4 unless $opt_p;

$opt_s=100000 unless $opt_s;

$opt_n=1000 unless $opt_n;

return(0);

}

Sharing_large_arrays_among_multiple_threads

(See the bioperl-l discussion http://lists.open-bio.org/pipermail/bioperl-l/2008-December/028777.html. See also Counting k-mers in large sets of large sequences.)

Marco Blanchette poses:

'’I am using the Perl threads utility to successfully multi threads several of my computing jobs on my workstation. My current problem is that I need to perform multiple processes using the same humongous array (more than 2 X 106 items). My problem is that the computing time for each iteration is not very long but I have a lot of iterations to do and every time a thread is created I am passing the huge array to the function and a fresh copy of the array is created. Thus, there is a huge amount of wasted resources (time and memory) use to create these data structures that are used by each threads but not modified.

'’The logical alternative is to use shared memory where all thread would have access to the same copy of the huge array. In principle Perl provide such a mechanism through the module (threads::shared) but I am unable to understand how to use the shared variables. Anyone has experience to share on threads::shared?’’

Jonathan Crabtree responds:

Here is a short test program, which runs correctly on perl 5.8.8 and may help to illustrate how the Perl threads::shared module expects you to create and share nested data structures. You have to manually share any nested references and I think that the order in which the sharing calls are made may also be significant:

#!/usr/bin/perl

use strict;

use warnings;

use threads;

use threads::shared;

# threads::shared test/demo program

# creates a shared 2-dimensional array and checks that it can be seen in a thread

# tested in perl v5.8.8 built for i486-linux-gnu-thread-multi

## ----------------------------------------

## globals

## ----------------------------------------

# set the width and height of the 2d array to this value:

my $ARRAY_SIZE = 10;

## ----------------------------------------

## main program

## ----------------------------------------

# calls to &share take place in here, so a shared value is returned

my $array = &make_shared_array();

# print array contents before running thread

print "shared array before running thread:\n";

&check_and_print_array($array);

# run thread

my $thr = threads->create(\&do_the_job, $array);

my $retval = $thr->join();

print "join() returned: $retval\n";

# print array contents after running thread

print "shared array after running thread:\n";

&check_and_print_array($array);

exit(0);

## ----------------------------------------

## subroutines

## ----------------------------------------

sub make_shared_array {

# outermost array object must be made shared first

my $a = &share([]);

for (my $i = 0;$i < $ARRAY_SIZE;++$i) {

# each of the rows must be explicitly shared

my $row = &share([]);

# and then added to the containing array

$a->[$i] = $row;

# assign each cell a unique integer for verification purposes

my $base = $i * $ARRAY_SIZE;

for (my $j = 0;$j < $ARRAY_SIZE;++$j) {

$row->[$j] = $base + $j;

}

}

return $a;

}

# print out the array, checking that its dimensions match what we expect

sub check_and_print_array {

my $arr = shift;

die "not an array" if ((ref $arr) ne 'ARRAY');

my $nr = scalar(@$arr);

die "wrong number of rows in array" if ($nr != $ARRAY_SIZE);

for (my $i = 0;$i < $nr;++$i) {

my $row = $arr->[$i];

die "row $i not an array" if ((ref $row) ne 'ARRAY');

my $nc = scalar(@$row);

die "wrong number of columns in row $i" if ($nc != $ARRAY_SIZE);

for (my $j = 0;$j < $nc;++$j) {

my $val = $row->[$j];

printf("%10s", $val);

}

print "\n";

}

}

# work to execute in the thread

sub do_the_job {

my $var = shift;

# print the array once more in the thread

print "shared array in thread:\n";

&check_and_print_array($var);

return "do_the_job returned ok";

}

When I run it (on Ubuntu) the output looks like this:

shared array before running thread:

0 1 2 3 4 5 6

7 8 9

10 11 12 13 14 15 16

17 18 19

20 21 22 23 24 25 26

27 28 29

30 31 32 33 34 35 36

37 38 39

40 41 42 43 44 45 46

47 48 49

50 51 52 53 54 55 56

57 58 59

60 61 62 63 64 65 66

67 68 69

70 71 72 73 74 75 76

77 78 79

80 81 82 83 84 85 86

87 88 89

90 91 92 93 94 95 96

97 98 99

shared array in thread:

0 1 2 3 4 5 6

7 8 9

10 11 12 13 14 15 16

17 18 19

20 21 22 23 24 25 26

27 28 29

30 31 32 33 34 35 36

37 38 39

40 41 42 43 44 45 46

47 48 49

50 51 52 53 54 55 56

57 58 59

60 61 62 63 64 65 66

67 68 69

70 71 72 73 74 75 76

77 78 79

80 81 82 83 84 85 86

87 88 89

90 91 92 93 94 95 96

97 98 99

join() returned: do_the_job returned ok

shared array after running thread:

0 1 2 3 4 5 6

7 8 9

10 11 12 13 14 15 16

17 18 19

20 21 22 23 24 25 26

27 28 29

30 31 32 33 34 35 36

37 38 39

40 41 42 43 44 45 46

47 48 49

50 51 52 53 54 55 56

57 58 59

60 61 62 63 64 65 66

67 68 69

70 71 72 73 74 75 76

77 78 79

80 81 82 83 84 85 86

87 88 89

90 91 92 93 94 95 96

97 98 99

I haven’t verified that doing this actually yields the memory savings you’re looking for, but I don’t see why it shouldn’t.

I

IO

Chromosomes_from_an_.agp_file_plus_contigs

(see bioperl-l here http://lists.open-bio.org/pipermail/bioperl-l/2009-January/028884.html and here http://lists.open-bio.org/pipermail/bioperl-l/2009-January/028887.html)

The sound of one man coding…

Russell Smithies asks the rhetorical question:

Does anyone have a script for building chromosomes from an .agp file and a directory full of contigs?

and his answer:

use Bio::DB::Fasta;

use Bio::Seq;

use Bio::SeqIO;

open(AGP,"Mt2.0_pgp.agp") or die $!;

my @chr = ();

my $db = Bio::DB::Fasta->new("contigs.fa");

while(<AGP>){

chomp;

split /\s/;

# extend temp string if it's too short

do{$chr[$_[0]] .= ' ' x 1_000_000;}while length $chr[$_[0]] < $_[2];

if($_[4] !~ m/N/){

($start,$stop) = $_[8] eq '+'?($_[6], $_[7]):($_[7], $_[6]);

$s = substr $chr[$_[0]], $_[1], $_[9], $db->seq($_[5],$start,$stop);

}else{

$s = substr $chr[$_[0]], $_[1], $_[5], "N" x $_[5] ;

}

}

#remove any trailing whitespace

@chr = map{s/\s+//g;$_}@chr;

#print the sequence. chromosomes are chr0 -> chr8

foreach(0..$#chr){

my $seqobj = Bio::Seq->new( -display_id => "chr$_", -seq => $chr[$_]);

my $seq_out = Bio::SeqIO->new('-file' => ">chr$_.fa",'-format' => 'fasta');

$seq_out->write_seq($seqobj);

}

Russell adds: * Please excuse my hacky use of substrings but this .agp file had overlapping runs of ‘N’ and this was the easiest way to deal with it; e.g.*

0 1 50000 1 N 50000 clone yes

0 50001 167645 2 F AC144644.3 1 117645 + 117645

0 167646 217645 3 N 50000 clone yes

0 217646 317645 4 N 100000 contig no

0 317646 367645 5 N 50000 clone yes

0 367646 411754 6 F AC146805.17 1 44109 + 44109

Converting_alignment_files

This script will convert an alignment file to another alignment file format. I use it to convert Mauve xmfa output to a directory of fasta alignments, but it is useful for converting fasta to clw or other formats.

Sorry if someone already wrote this kind of script… I couldn’t find one like it right away, so I made it and thought I should contribute. –Lskatz 18:24, 21 February 2012 (UTC)

I updated my script. There are two major things in this that I think I updated over time which is error reporting and also the ability to concatenate an entire xmfa into a fasta alignment. Some people in my lab wanted to view a MAUVE alignment in MEGA, which prompted this. –Lskatz 20:10, 3 August 2012 (UTC)

The newest version of the script will be at my github page but I will leave this version here for posterity. –Lskatz 14:39, 29 December 2014 (UTC) https://github.com/lskatz/lskScripts

#!/usr/bin/env perl

# Converts an alignment to another alignment format

# Run with no arguments or with -h for help.

# author: Lee Katz <lkatz@cdc.gov>

use Bio::AlignIO;

use strict;

use warnings;

use Getopt::Long;

use <Data::Dumper>;

use List::Util qw/max/;

sub logmsg{print "@_ ";};

exit(main());

sub main{

my $settings={};

die usage() if(@ARGV<1);

GetOptions($settings,qw(infile=s ginformat=s outfile=s format=s concatenateAlignment linker=s));

die usage() if($$settings{help});

my $infile=$$settings{infile} or die "Error: Need infile param:\n".usage();

my $outfile=$$settings{outfile} or die "Error: Need outfile param:\n".usage();

$$settings{outfileformat}=$$settings{format} || "fasta";

$$settings{linker}||="";

convertAln($infile,$outfile,$settings);

logmsg "Output is now in $outfile";

return 0;

}

sub convertAln{

my($infile,$outfile,$settings)=@_;

$$settings{infileFormat}=$$settings{ginformat}||guess_format($infile,$settings);

my $numAlns;

if($outfile=~/\/$/){

$numAlns=convertAlnToDir($infile,$outfile,$settings);

} else {

$numAlns=convertAlnToFile($infile,$outfile,$settings);

}

logmsg "Finished converting $infile to $outfile ($numAlns alignments)";

return $numAlns;

}

sub convertAlnToDir{

my($infile,$outdir,$settings)=@_;

$outdir=~s/\/+$//; # remove the trailing slash

logmsg "Converting $infile ($$settings{infileFormat}) to a directory $outdir ($$settings{outfileformat})";

mkdir($outdir) if(!-d $outdir);

my $in=Bio::AlignIO->new(-file=>$infile,-format=>$$settings{infileFormat});

my $alnCounter=0;

my $outExtension=$$settings{outfileformat};

while(my $aln=$in->next_aln){

my $out=Bio::AlignIO->new(-file=>">$outdir/".++$alnCounter.$outExtension,-format=>$$settings{outfileformat},-flush=>0);

$out->write_aln($aln);

}

return $alnCounter;

}

sub convertAlnToFile{

my($infile,$outfile,$settings)=@_;

logmsg "Converting $infile ($$settings{infileFormat}) to file $outfile";

my $in=Bio::AlignIO->new(-file=>$infile,-format=>$$settings{infileFormat});

my $out=Bio::AlignIO->new(-file=>">$outfile",-format=>$$settings{outfileformat},-flush=>0);

my $alnCounter=0;

if($$settings{concatenateAlignment}){

my @expectedId=findAllUniqueIdsInAln($infile,$settings);

my %alnSequence;

while(my $aln=$in->next_aln){

# concatenate sequences

foreach my $seq($aln->each_seq){

$alnSequence{$seq->id}.=$seq->seq.$$settings{linker};

}

# keep the alignment flush, even if I have to add gaps

my $currentAlnLength=max(map(length($_),values(%alnSequence)));

for(@expectedId){

my $lackOfSequence=$currentAlnLength-length($alnSequence{$_});

$alnSequence{$_}.='-'x$lackOfSequence;

}

}

# write the complete alignment to a file

my $concatAln=Bio::SimpleAlign->new();

for(@expectedId){

my $stringfh;

open($stringfh, "<", $alnSequence{$_}) or die "Could not open string for reading: $!";

my $seq=new Bio::LocatableSeq(-seq=>$alnSequence{$_},-id=>$_); # must be locatableSeq to be added

$concatAln->add_seq($seq);

}

$out->write_aln($concatAln);

} else { # it's pretty simple to just do a conversion to a different file

while(my $aln=$in->next_aln){

$out->write_aln($aln);

$alnCounter++;

}

}

return $alnCounter;

}

sub findAllUniqueIdsInAln{

my($infile,$settings)=@_;

logmsg "Finding all expected sequence IDs";

my %genome;

my $alnin=Bio::AlignIO->new(-file=>$infile,-format=>$$settings{infileFormat});

while(my $aln=$alnin->next_aln){

foreach my $seq($aln->each_seq){

$genome{$seq->id}++;

}

}

return keys(%genome);

}

sub guess_format{

my ($filename,$settings)=@_;

for my $format (qw(pfam xmfa selex fasta stockholm prodom clustalw msf mase bl2seq nexus phylip)){

eval{

my $in=Bio::AlignIO->new(-file=>$filename,-format=>$format);

my $aln=$in->next_aln;

$aln->length;

};

if($@){

my $error=$@;

next;

}

return $format;

}

die "Could not guess the format of $filename\n";

}

sub usage{

"Converts an alignment to another alignment format.

$0 -i alignmentfile -o outputPrefix [-f outputformat]

-i the alignment file to input

-o the output alignment file or directory

Specify a directory by a trailing slash.

If a directory, the output format will be determined by -f. Default: fasta.

-f output format

possible values are derived from bioperl.

e.g. fasta, clustalw, phylip, xmfa

-g input format to force the correct input format, but it's ok to let it guess

-c to concatenate the alignment into one solid entry

-l linkerSequence, to be used with -c, to separate entries.

Default is no linker but a useful linker could be NNNNNNNNNN

-h this helpful menu

";

}

Converting_FASTQ_to_FASTA_QUAL_files

I came up with a script to accompany Minimo, which is a nice assembler that can be fed by Illumina reads (but it doesn’t read FASTQ). Therefore there needs to be a fast way to convert FASTQ to FASTA/QUAL. This script is multithreaded and works best as you approach the number of CPUs you have. It is untested on non-threaded installations of Perl.

There is a method to perform the opposite operation: Merging separate sequence and quality files to FASTQ

Usage: $0 -i inputFastqFile [-n numCpus -q outputQualfile -f outputFastaFile]

#!/usr/bin/env perl

# Author: Lee Katz

# Convert a fastq to a fasta/qual combo using BioPerl, with some Linux commands

use Bio::Perl;

use Data::Dumper;

use strict;

use warnings;

use threads;

use Thread::Queue;

use Getopt::Long;

my $settings={};

$|=1;

my %numSequences; # static for a subroutine

exit(main());

sub main{

die("Usage: $0 -i inputFastqFile [-n numCpus -q outputQualfile -f outputFastaFile]") if(@ARGV<1);

GetOptions($settings,('numCpus=s','input=s','qualOut=s','fastaOut=s'));

my $file=$$settings{input}||die("input parameter missing");

my $outfasta=$$settings{fastaOut}||"$file.fasta";

my $outqual=$$settings{qualOut}||"$file.qual";

my $numCpus=$$settings{numCpus}||1;

my @subfile=splitFastq($file,$numCpus);

for my $f(@subfile){

threads->create(&convert,$f,"$f.fasta","$f.qual");

}

$_->join for (threads->list);

# join the sub files together

joinFastqFiles(\@subfile,$file);

return 0;

}

sub convert{

my($file,$outfasta,$outqual)=@_;

my $numSequences=numSequences($file);

my $reportEvery=int($numSequences/100) || 1;

print "$numSequences sequences to convert in $file\n";

my $in=Bio::SeqIO->new(-file=>$file,-format=>"fastq-illumina");

my $seqOut=Bio::SeqIO->new(-file=>">$outfasta",-format=>"fasta");

my $qualOut=Bio::SeqIO->new(-file=>">$outqual",-format=>"qual");

my $seqCount=0;

my $percentDone=0;

while(my $seq=$in->next_seq){

$seqOut->write_seq($seq);

$qualOut->write_seq($seq);

$seqCount++;

if($seqCount%$reportEvery == 0){

$percentDone++;

print "$percentDone%..";

}

}

print "Done with subfile $file.\n";

return 1;

}

sub joinFastqFiles{

my($subfile,$outfileBasename)=@_;

my($command,$subfasta,$subqual);

# fasta

$subfasta.="$_.fasta " for(@$subfile);

$command="cat $subfasta > $outfileBasename.fasta";

system($command);

# qual

$subqual.="$_.qual " for (@$subfile);

$command="cat $subqual > $outfileBasename.qual";

system($command);

return 1;

}

sub splitFastq{

my($file,$numCpus)=@_;

my $prefix="FQ"; # for fastq

my $numSequences=numSequences($file);

my $numSequencesPerFile=int($numSequences/$numCpus);

my $numSequencesPerFileRemainder=$numSequences % $numCpus;

my $numLinesPerFile=$numSequencesPerFile*4; # four lines per read; this could become incorrect if there is a really long read (not currently likely)

system("rm -r tmp;mkdir tmp;");

system("split -l $numLinesPerFile $file 'tmp/FQ'");

return glob("tmp/FQ*");

}

# use Linux to find the number of sequences quickly, but cache the value because it is still a slow process

# This should probably changed to `wc -l`/4 but I don't have time to test the change

# TODO for anyone reading this: please change this method to wc -l divided by 4.

sub numSequences{

my $file=shift;

return $numSequences{$file} if($numSequences{$file});

my $num=`grep -c '^\@' $file`;

chomp($num);

$numSequences{$file}=$num;

return $num;

}

Getting_Fasta_sequences_from_a_GFF

Some have whimpered, “How do I get a fasta file of the features in this GFF?”… Well, assuming your GFF file fits into memory (and assuming you have the appropriate fasta file to hand), here’s how:

A script I like to call gff2fasta

#!/usr/bin/perl -w

use strict;

use Bio::SeqIO;

my $verbose = 0;

# read in gff

warn "reading GFF ";

my %gff;

open GFF, '<', 'my.gff3'

or die "fail\n";

while(<GFF>){

my ($seqid, undef, undef, $start, $end,

undef, undef, undef, $attrs) = split;

push @{$gff{$seqid}}, [$start, $end, $attrs];

}

warn "OK\n";

# Do the fasta

my $seqio = Bio::SeqIO->

new( -file => 'my.fa',

-format => 'fasta' )

or die "double fail\n";

while(my $sobj = $seqio->next_seq){

my $seqid = $sobj->id;

unless(defined($gff{$seqid})){

warn "no features for $seqid\n";

next;

}

my $seq = $sobj->seq;

for(@{$gff{$seqid}}){

my ($start, $end, $attrs) = @$_;

warn join("\t", $start, $end, $attrs), "\n"

if $verbose > 0;

my %attrs = split(/=|;/, $attrs);

print ">$seqid-". $attrs{"ID"}.

"/$start-$end (". ($end-$start+1). ")\n";

print substr($seq, $start, $end-$start+1), "\n";

}

#exit;

}

warn "OK\n";

Merging_separate_sequence_and_quality_files_to_FASTQ

(see the bioperl-l thread starting here , and also look at this for the hard way)

Dan Bolser opines:

I have a ‘fasta quality file’ and a fasta file, and I would like to output a fastq file…I get the feeling that this should be a one-liner.

- Almost, as Dan discovered, producing the following scrap (with a nod to Phillip San Miguel):

#!/usr/bin/perl -w

use strict;

use Bio::SeqIO;

use Bio::Seq::Quality;

use Getopt::Long;

die "pass a fasta and a fasta-quality file "

unless @ARGV;

my ($seq_infile,$qual_infile)

= (scalar @ARGV == 1) ?($ARGV[0], "$ARGV[0].qual") : @ARGV;

# Create input objects for both a seq (fasta) and qual file

my $in_seq_obj =

Bio::SeqIO->new( -file => $seq_infile,

-format => 'fasta',

);

my $in_qual_obj =

Bio::SeqIO->new( -file => $qual_infile,

-format => 'qual',

);

my $out_fastq_obj =

Bio::SeqIO->new( -format => 'fastq'

);

while (1){

## create objects for both a seq and its associated qual

my $seq_obj = $in_seq_obj->next_seq || last;

my $qual_obj = $in_qual_obj->next_seq;

die "foo!\n"

unless

$seq_obj->id eq

$qual_obj->id;

## Here we use seq and qual object methods feed info for new BSQ

## object.

my $bsq_obj =

Bio::Seq::Quality->

new( -id => $seq_obj->id,

-seq => $seq_obj->seq,

-qual => $qual_obj->qual,

);

## and print it out.

$out_fastq_obj->write_fastq($bsq_obj);

}

For more information, see Bio::Seq::Quality.

Parsing_BLAST_HSPs

(see bioperl-l thread here)

The key to parsing any external program report is knowing where (i.e., in what BioPerl object) the stuff you want lives. This info can be tricky to find, though walking through the code to find it is an excellent exercise for learning how BioPerl is structured.

Below is some code to get BLAST high-scoring pairs from a BLAST report. Here is the basic BP-object structure:

- $report is-a Bio::SearchIO::blast, which contains

- $result is-a Bio::Search::Result::BlastResult, which contains

- $hit is-a Bio::Search::Hit::BlastHit, which contains

- $hsp is-a Bio::Search::HSP::GenericHSP

- $hit is-a Bio::Search::Hit::BlastHit, which contains

- $result is-a Bio::Search::Result::BlastResult, which contains

As a professor (David Wollkind) of mine once said (while teaching the chain rule), you have to peel away the players until you find the one with the ball.

Note there are many accessors on the Bio::Search::HSP::GenericHSP object though which the interesting stuff can be obtained.

The scrap uses blastn to align two sequences. Get the standalone BLAST programs from NCBI (they don’t come with BioPerl!).

–MAJ

#!/usr/bin/perl -w

use strict;

use Bio::SeqIO;

use Bio::Tools::Run::StandAloneBlast;

my $query1_in = Bio::SeqIO->newFh ( -file => "mus-betaglobin-bh0.fas",

-format => 'fasta' );

my $query1 = <$query1_in>;

my $query2_in = Bio::SeqIO->newFh ( -file => "mus-betaglobin-bh3.fas",

-format => 'fasta' );

my $query2 = <$query2_in>;

$factory = Bio::Tools::Run::StandAloneBlast->new('program' => 'blastn');

$report = $factory->bl2seq($query1, $query2);

while (my $result = $report->next_result) {

print "Query: ".$result->query_name."\n";

while (my $hit = $result->next_hit) {

while ($hsp = $hit->next_hsp) {

print $hsp->algorithm, ": identity ", 100*$hsp->frac_identical, "\%, rank ", $hsp->rank, " (E:", $hsp->evalue, ")\n";

printf("%7s: %s\n", "subj", $hsp->query_string);

printf("%7s: %s\n", "", $hsp->homology_string);

printf("%7s: %s\n", "hom", $hsp->hit_string);

print "\n";

}

print "\n";

}

}

Parsing_BLAST_results_into_per-query_files

- Remember that can write as well as read. –Ed.

Tim Kohler asks:

When I use Bio::Tools::Run::StandAloneBlast to BLAST one fasta file including different sequences, I get a BLAST output with many queries, each having several hits / sbjcts. My problem is how to parse all hits of one query into a single new file. And this for all the queries I have in my BLAST output file.

If you have your multiple-query blast report file, you can sort and output separate files like so:

use Bio::Search::Result::BlastResult;

use Bio::SearchIO;

my $report = Bio::SearchIO->new( -file=>'full-report.bls', -format =>

blast);

my $result = $report->next_result;

my %hits_by_query;

while (my $hit = $result->next_hit) {

push @{$hits_by_query{$hit->name}}, $hit;

}

foreach my $qid ( keys %hits_by_query ) {

my $result = Bio::Search::Result::BlastResult->new();

$result->add_hit($_) for ( @{$hits_by_query{$qid}} );

my $blio = Bio::SearchIO->new( -file => ">$qid\.bls", -format=>'blast' );

$blio->write_result($result);

}

–Ed.

Russell also had a solution, but we’ll let him pare it down for the scrapbook!

Preparing_contigs_for_GenBank_submission

(see bioperl-l thread starting here)

- The key issue in this scrap is how creating a GenBank record for a Bio::DB::GFF persisted object is not quite as simple as reading from the DB and writing to SeqIO. Read on for the particulars (responses are from Jason Stajich and Don Gilbert). –Ed.

Erich Schwarz discusses contig submissions sans Sequin:

I have newly sequenced contigs, with CDS predictions, loaded loaded into a MySQL database via Bio::DB::GFF. I’d like to export each contig, with its annotated CDSes, into a single GenBank-formatted record for each contig.

and notes the following:

I came up with code that would let me export protein translations of the contigs’ CDSes in GenBank format…

use strict;

use warnings;

use Bio::Seq;

use Bio::SeqIO;

use Bio::DB::GFF;

my $query_database = $ARGV[0];

my $dna = q{};

my $db = Bio::DB::GFF->new( -dsn => $query_database);

my $gb_file = 'example.gb';

my $seq_out = Bio::SeqIO->new( -file => ">$gb_file", -format => 'genbank');

my @contigs = sort

map { $_->display_id }

$db->features( -types => 'contig:assembly' );

foreach my $contig (@contigs) {

my $segment1 = $db->segment($contig);

my @p_txs = $segment1->features('processed_transcript');

foreach my $p_t (sort @p_txs) {

$dna = q{};

my @CDSes = $p_t->CDS;

my $cds_name = $CDSes[0]->display_id();

foreach my $cds (@CDSes) {

# $cds->seq == Bio::PrimarySeq, *not* plain nt seq.!

$dna = $dna . $cds->seq->seq;

}

my $full_cds = Bio::Seq->new( -display_id => $cds_name,

-seq => $dna, );

my $prot = $full_cds->translate;

$seq_out->write_seq($prot);

}

}

Returning to this, I tried using $db->get_Seq_by_id($contig) to give me a Bio::Seq object for each contig (which I could then output into GenBank form), but that proved futile.

Jason Stajich provides some details:

If you want to get a specific segment you just do what you already have in your code:

my $segment = $db->segment($contig_name);

Or you can iterate through all the features - depends on how you named your segments/contigs/chromsomes, I named mine “contig:scaffold” for type:source:

my $iterator = $dbh->get_seq_stream(-type=>'scaffold');

while (my $s = $iterator->next_seq) {

...

}

Now you should be able to pass this segment object to

$seqio->write_seq($segment);

However, Bio::DB::GFF::Feature doesn’t implement the whole Bio::SeqI API so you probably have to create your own sequence and move the features over:

my $iterator = $dbh->get_seq_stream(-type=>'scaffold');

while (my $s = $iterator->next_seq) {

my $seq = Bio::Seq->new();

$seq->primary_seq($s->seq);

for my $feature ( $s->features('processed_transcript') ) {

my $f = Bio::SeqFeature::Generic->new(-location => $feature->location,

-primary_tag => $feature->primary_tag,

-source_tag => $feature->primary_tag,

-score => $feature->score,

-seq_id => $feature->seq_id);

$f->add_tag_value('locus_tag',$feature->name);

# might also add all other tag/value pairs from this feature like

# DBXREF, etc.

# can derive a CDS feature from this feature as well.

# or perhaps derive a gene feature that only has start/end for the feature

# or might add a translation tag/value pair for CDS features

$seq->add_SeqFeature($f);

}

$out->write_seq($seq);

}

I suspect you’ll have to edit the feature objects some to a) remove the ones you don’t want to output, b) add additional info like translation frame…, c) add in other annotation information that may or may not be encoded as tag/values that NCBI requires.

Don Gilbert suggests persisting in Chado rather than Bio::DB::GFF:

If the Bio::DB::GFF database to Genbank submission route doesn’t get you where you want, you can also look at storing your data in a GMOD Chado database, then using Bulkfiles to produce the Genbank Submission file set.

Find a GenBank Submit output from Chado dbs in this tool release

GMODTools-1.2b.zip 20-Jun-2008

adding (in progress) the Genbank Submission table writer, bulkfiles -format=genbanktbl, with output suited to submit to NCBI per these specifications

See also the GMODTools wiki and this test case with genbank-submit output.

M

Metadata

Features_vs._Annotations

(see bioperl-l thread here)

- This scrap tries to codify a discussion on the differences between SeqFeatures and Annotations in the BioPerl world. The brains behind it are those of Chris Fields and Hilmar Lapp. –Ed.

The Issue

Govind Chandra raises the following issue, based on the code below ($ac is the Bio::Annotation::Collection property of a Bio::Seq object obtained from a Bio::SeqIO stream). The reply is here:

$ac is-a Bio::Annotation::Collection but does not actually contain any annotation from the feature. Is this how it should be? I cannot figure out what is wrong with the script. Earlier I used to use has_tag(), get_tag_values() etc. but the documentation says these are deprecated.

Sample code:

#use strict;

use Bio::SeqIO;

$infile='NC_000913.gbk';

my $seqio=Bio::SeqIO->new(-file => $infile);

my $seqobj=$seqio->next_seq();

my @features=$seqobj->all_SeqFeatures();

my $count=0;

foreach my $feature (@features) {

unless($feature->primary_tag() eq 'CDS') {next;}

print($feature->start()," ", $feature->end(), " ",$feature->strand(),"\n");

$ac=$feature->annotation();

$temp1=$ac->get_Annotations("locus_tag");

@temp2=$ac->get_Annotations();

print("$temp1 $temp2[0] @temp2\n");

if($count++ > 5) {last;}

}

print(ref($ac),"\n");

exit;

Output:

190 255 1

0

337 2799 1

0

2801 3733 1

0

3734 5020 1

0

5234 5530 1

0

5683 6459 -1

0

6529 7959 -1

0

Bio::Annotation::Collection

The Response

- This is a mash-up of the responses from Chris and Hilmar, with some expansion and elision by your humble scribe. Please follow the thread for the verbatim responses in context. Also, see the much more detailed Feature-Annotation HOWTO.

Features vs. Annotations

In imprecise “user-centric” terms, a feature is metadata attached to a particular section or fragment of a sequence, while an annotation is metadata attached to the sequence object itself, and so describes something about the entire sequence.

In more precise, “implementor-centric” terms, an annotation object is something that you would like to attach to an annotatable object. The reason you want to attach it (and any semantics implied by that reason) is in the tag. The implementation principle that captures the “user-centric” idea is:

- A feature is (and in the BioPerl-way of looking at the world, should be) locatable, whereas annotation is not.

Who accesses what, from where?

The typical use case is as follows:

- Download a GenBank file

- Access the file as a stream using Bio::SeqIO

- Pull a Bio::Seq object from the stream using Bio::SeqIO::next_seq

- Read GenBank features/annotations from the Bio::Seq object using object methods

For the user, the question arises, “How do I get at these furshlugginer annotations??” Perhaps it’s better to ask “How do I get at these furshlugginer metadata?? “, since separating features and annotations in the mind according to the ideas above will help the user look in the right place for the metadata desired. Expletives are optional.

The Bio::SeqIO object (call it $seq) contains an annotation property (a Bio::Annotation::Collection object) accessed via $seq->annotation(). It also contains feature properties, accessed by methods such as $seq->get_SeqFeatures, which return Bio::SeqFeatureI objects. These feature objects are generally instantiated in the Bio::SeqFeature::Generic class, where most of the accessors the average user desires reside.

The Short Answer

A user often wants to parse the features: start and end coordinates, strand, locus name, source, etc. So the short answer to the user’s question is often something like the following (lifted directly from the Bio::Seq POD):

# This block of code loops over sequence features in the sequence

# object, trying to find ones who have been tagged as 'exon'.

# Features have start and end attributes and can be outputted

# in Genbank Flat File format, GFF, a standarized format for sequence

# features.

foreach $feat ( $seqobj->get_SeqFeatures() ) {

if( $feat->primary_tag eq 'exon' ) {

print STDOUT "Location ",$feat->start,":",

$feat->end," GFF[",$feat->gff_string,"]\n";

}

}

Note that the features are obtained from the feature accessor of the sequence object, and the tags associated with each feature are obtained by using the tag accessors off the feature objects.

The Details

The key thing to notice here is that the feature objects and not the annotation objects are read. There was a time (see the History below) when the tag accession methods could be called off the annotation object. This behavior is now deprecated, in part to get people used to making the distinctions being discussed here.

However, remember that in “implementor-centric” terms, an annotation object is something that you would like to attach to an annotatable object. So… $feat->annotation() is a legitimate method call, since Bio::SeqFeatureI implements Bio::AnnotatableI.

As Hilmar states:

- SeqFeature::Generic has indeed two mechanisms to store annotation, the tag system and the annotation collection. This is because it inherits from

SeqFeatureI(which brings in the tag/value annotation) and fromAnnotatableI(which brings inannotation()).

I agree this can be confusing from a user’s perspective. As a rule of thumb, SeqIO parsers will almost universally populate only the tag/ value system, because typically they will (or should) assume not more than that the feature object they are dealing with is a SeqFeatureI.

Once you have the feature objects in your hands, you can add to either tag/values or annotation() to your heart’s content. Just be aware that nearly all SeqIO writers won’t use the annotation() collection when you pass the sequence back to them since typically they won’t really know what to do with feature annotation that isn’t tag/value (unlike as for sequence annotation).

If in your code you want to treat tag/value annotation in the same way as (i.e., as if it were part of) the annotation that’s in the annotation collection then use Bio::SeqFeature::AnnotationAdaptor. That’s in fact what BioPerl db does to ensure that all annotation gets serialized to the database no matter where it is.

However, unless expressly told otherwise in a parser documentation, a sequence you get back from one of the SeqIO parsers (which is where most people will get them from) will not have $feat->annotation() populated.

The Best of Both Worlds : Bio::SeqFeature::AnnotationAdaptor

If you want to get all the metadata for a sequence object, and don’t care (implementation-wise) where it comes from, use Bio::SeqFeature::AnnotationAdaptor:

# (of hilmar)

my $anncoll = Bio::SeqFeature::AnnotationAdaptor->new();

foreach my $feat ($seq->get_all_SeqFeatures) {

$anncoll->feature($feat);

@vals = $anncoll->get_Annotations('locus_tag');

# do something with @vals

}

The description of SeqFeature::AnnotationAdaptor from its POD summarizes its raison d'etre, and conveys another important distinction between Bio::SeqFeatureI and Bio::AnnotationCollectionI:

- Bio::SeqFeatureI defines light-weight annotation of features through tag/value pairs. Conversely, Bio::AnnotationCollectionI together with Bio::AnnotationI defines an annotation bag, which is better typed, but more heavy-weight because it contains every single piece of annotation as objects. The frequently used base implementation of Bio::SeqFeatureI, Bio::SeqFeature::Generic, defines an additional slot for AnnotationCollectionI-compliant annotation.

This adaptor provides a Bio::AnnotationCollectionI compliant, unified, and integrated view on the annotation of Bio::SeqFeatureI objects, including tag/value pairs, and annotation through the annotation() method, if the object supports it. Code using this adaptor does not need to worry about the different ways of possibly annotating a SeqFeatureI object, but can instead assume that it strictly follows the AnnotationCollectionI scheme. The price to pay is that retrieving and adding annotation will always use objects instead of light-weight tag/value pairs.

In other words, this adaptor allows us to keep the best of both worlds. If you create tens of thousands of feature objects, and your only annotation is tag/value pairs, you are best off using the features’ native tag/value system. If you create a smaller number of features, but with rich and typed annotation mixed with tag/value pairs, this adaptor may be for you. Since its implementation is by double- composition, you only need to create one instance of the adaptor. In order to transparently annotate a feature object, set the feature using the feature() method. Every annotation you add will be added to the feature object, and hence will not be lost when you set feature() to the next object.

See the thread for a nice extended metaphor involving Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups. This shouldn’t, of course, be construed as an endorsement for them. (Extended metaphors, that is.)

A History of BioPerl Annotation (Chris Fields)

To go over why things were set up this way (and then reverted), is a bit of a history lesson. I believe prior to 1.5.0, Bio::SeqFeature::Generic stored most second-class data (dbxrefs, simple secondary tags, etc) as simple untyped text via tags but also allowed a Bio::Annotation::Collection. Therefore one effectively gets a mixed bag of first-class untyped data like display_id and primary_tag, untyped tagged text, and ‘typed’ Bio::AnnotationI objects.

Some of this was an attempt to somewhat ‘correct’ this for those who wanted a cohesive collection of typed data out-of-the-box. Essentially, everything becomes a Bio::AnnotationI. I believe Bio::SeqFeature::Annotated went a step further and made almost everything Bio::AnnotationI (including score, primary_tag, etc.) and type-checked tag data against SOFA.

As there were collisions between SeqFeature-like ‘tag’ methods and CollectionI-like methods, the design thought was to store all tag data as Bio::Annotation in a Bio::Annotation::Collection, then eventually deprecate the tag methods in favor of those available via the CollectionI. These deprecations were placed in Bio::AnnotatableI, so any future Bio::SeqFeatureI implementations would also get the deprecation. As noted, Bio::SeqFeature::Generic implements these methods so isn’t affected.

Now, layer in the fact that many of these (very dramatic) code changes were literally introduced just prior to the 1.5.0 release, AFAIK w/o much code review, and contained additional unwanted changes such as operator overloading and so on. Very little discussion about this occurred on list until after the changes were introduced (a good argument for small commits). Some very good arguments against this were made, including other lightweight implementations. Lots of angry devs!

Though the intentions were noble we ended up with a mess. I yanked these out a couple of years ago frankly out of frustration with the overloading issues.

N

Nextgen_Sequencing

Lee_Katz_detectPeReads

Detecting Paired End reads. This doesn’t really use BioPerl but I had a hard time finding a subroutine for this and wanted to share with the community. Any additions are welcome. –Lskatz 19:45, 19 June 2014 (UTC)

Updated to streamline it and also because it was pointed out that in Casava1.8 there can be alternatives to the 1/2 pairing, e.g., 1/3, which would indicate that the multiplex tags are present somewhere (but not in the query fastq file) –Lskatz 18:05, 8 July 2014 (UTC)

# See whether a fastq file is paired end or not. It must be in a velvet-style shuffled format.

# In other words, the left and right sides of a pair follow each other in the file.

# params: fastq file and settings

# fastq file can be gzip'd

# settings: checkFirst is an integer to check the first X deflines

# TODO just extract IDs and send them to the other _sub()

sub is_fastqPE($;$){

my($fastq,$settings)=@_;

# if checkFirst is undef or 0, this will cause it to check at least the first 20 entries.

# 20 reads is probably enough to make sure that it's shuffled (1/2^10 chance I'm wrong)

$$settings{checkFirst}||=20;

$$settings{checkFirst}=20 if($$settings{checkFirst}<2);

# get the deflines

my @defline;

my $numEntries=0;

my $i=0;

my $fp;

if($fastq=~/\.gz$/){

open($fp,"gunzip -c '$fastq' |") or die "Could not open $fastq for reading: $!";

}else{

open($fp,"<",$fastq) or die "Could not open $fastq for reading: $!";

}

my $discard;

while(my $defline=<$fp>){

next if($i++ % 4 != 0);

chomp($defline);

$defline=~s/^@//;

push(@defline,$defline);

$numEntries++;

last if($numEntries > $$settings{checkFirst});

}

close $fp;

# it is paired end if it validates with any naming system

my $is_pairedEnd=_is_fastqPESra(\@defline,$settings) || _is_fastqPECasava18(\@defline,$settings) || _is_fastqPECasava17(\@defline,$settings);

return $is_pairedEnd;

}

sub _is_fastqPESra{

my($defline,$settings)=@_;

my @defline=@$defline; # don't overwrite $defline by mistake

for(my $i=0;$i<@defline-1;$i++){

my($genome,$info1,$info2)=split(/\s+/,$defline[$i]);

if(!$info2){

return 0;

}

my($instrument,$flowcellid,$lane,$x,$y,$X,$Y)=split(/:/,$info1);

my($genome2,$info3,$info4)=split(/\s+/,$defline[$i+1]);

my($instrument2,$flowcellid2,$lane2,$x2,$y2,$X2,$Y2)=split(/:/,$info3);

$_||="" for($X,$Y,$X2,$Y2); # these variables might not be present

if($instrument ne $instrument2 || $flowcellid ne $flowcellid2 || $lane ne $lane2 || $x ne $x2 || $y ne $y2 || $X ne $X2 || $Y ne $Y2){

return 0;

}

}

return 1;

}

sub _is_fastqPECasava18{

my($defline,$settings)=@_;

my @defline=@$defline;

for(my $i=0;$i<@defline-1;$i++){

my($instrument,$runid,$flowcellid,$lane,$tile,$x,$yandmember,$is_failedRead,$controlBits,$indexSequence)=split(/:/,$defline[$i]);

my($y,$member)=split(/\s+/,$yandmember);

my($inst2,$runid2,$fcid2,$lane2,$tile2,$x2,$yandmember2,$is_failedRead2,$controlBits2,$indexSequence2)=split(/:/,$defline[$i+1]);

my($y2,$member2)=split(/\s+/,$yandmember2);

# Instrument, etc must be the same.

# The member should be different, usually "1" and "2"

if($instrument ne $inst2 || $runid ne $runid2 || $flowcellid ne $fcid2 || $tile ne $tile2 || $member>=$member2){

return 0;

}

}

return 1;

}

# This format is basically whether the ends of the defline alternate 1 and 2.

sub _is_fastqPECasava17{

my($defline,$settings)=@_;

my @defline=@$defline;

for(my $i=0;$i<@defline-1;$i++){

# Get each member number but return false if it doesn't even exist.

my ($member1,$member2);

if($defline[$i] =~ m/(\d+)$/){

$member1=$1;

} else {

return 0;

}

if($defline[$i+1] =~ /(\d+)$/){

$member2=$1;

} else {

return 0;

}

# The test is whether member1 is less than member2.

# They can't be equal either.

if($member1 >= $member2){

return 0;

}

}

return 1;

}

Removing_sequencing_adapters

(See the bioperl-l threads here and here for discussion on next-gen modules)

This is some example code for the removal of sequencing adapters from next generation sequence reads. This is useful for cleaning up sequence from Solexa/Illumina GA machines, and may also be relevant for the removal of adapter/primer sequence from other types of sequence machine.

These code excerpts are from a prototype sequence pre-processing pipeline, and the approach described may soon become obsolete. This example code is functional, but not optimal. The first stage of the pipeline is to parse the sequence (with quality) and extract the good quality sequence. This must be done prior to using this method for adapter removal.

Before we start with the Bioperl, we align all of the good quality sequence (some.fasta) with the sequencing adapter (adapter.fasta) and output the alignments.

needle -gapopen 100 -gapextend 10 -auto -asequence adapter.fasta -bsequence stdin -outfile stdout < some.fasta > lots_of.aln

We don’t want any gaps, and Needle doesn’t support ungapped alignments, so we set the gap penalties as high as possible. Note that we don’t use Water, because we want to extract the sequence before the adapter, and so need the full sequences in the alignment output.

Now we have our alignments we can pipe them into our adapter removal script.

use Bio::AlignIO;

my $aln_in = Bio::AlignIO->new(-fh => \*STDIN, -format => 'emboss'); # clustalw format is a handy alternative for readability

while ( my $aln = $aln_in->next_aln ) {

# Get the coordinates of the start and end of the sequence and adapter in the alignment

my $r1 = Bio::Range->new( -start=> $aln->column_from_residue_number( $aln->get_seq_by_pos(1)->display_id, "1" ),

-end=> $aln->column_from_residue_number( $aln->get_seq_by_pos(1)->display_id, $aln->select(1,1)->no_residues ),

-strand=> +1);

my $r2 = Bio::Range->new( -start=> $aln->column_from_residue_number( $aln->get_seq_by_pos(2)->display_id, "1" ),

-end=> $aln->column_from_residue_number( $aln->get_seq_by_pos(2)->display_id, $aln->select(2,2)->no_residues ),

-strand=> +1);

my ($start, $end, $strand) = $r1->intersection($r2); # Coordinates where the sequence and adapter align

my $aln2 = $aln->slice($start, $end); # Get the alignment slice

# Neither Emboss nor Bio::Align::PairwiseStatistics offer a suitable scoring method for adapter removal, so here is one I made earlier

my @seq1 = split ("", $aln2->get_seq_by_pos(1)->seq);

my @seq2 = split ("", $aln2->get_seq_by_pos(2)->seq);

my ($score, $mismatches, $gaps) = qw (0 0 0);

for (my $pos = 0; $pos < $aln2->length; $pos++)

{

if ($seq1[$pos] eq $seq2[$pos]) { $score ++; } # Matches

elsif ($seq1[$pos] ne "N" && $seq2[$pos] ne "N") # Mismatches

{

$score --;

$mismatches ++;

}