This page describes some basic Git commands for working with the BioPerl source code.

You need to have the git client installed. Here is one set of instructions. Mac OSX download and install is easier here.

Git primer

Before you begin, you may consider reading these excellent primers put together by the Parrot project, which also apply quite well to BioPerl.

- Git Terminology guide (80% generic, 20% parrot specific).

- Git Workflow guide (80% generic, 20% parrot specific).

Download BioPerl from GitHub

To checkout (or clone) the BioPerl core package (most people only want the core package) from GitHub, use:

$ git clone git://github.com/bioperl/bioperl-live.git

Alternatively, you can checkout (or clone) a specific BioPerl package such as bioperl-db:

$ git clone git://github.com/bioperl/bioperl-db.git

Bioperl GitHub Repositories

| Link | Description |

|---|---|

| bioperl-live | Core package including parsers and main objects |

| bioperl-run | Wrapper package around key applications |

| bioperl-db | BioPerl DB is the Perl API that accesses the BioSQL schema |

| bioperl-dev | Bioperl-dev is a development repository for exploratory package |

| bioperl-ext | Ext package has C extensions including alignment routines and link to staden IO library for sequence trace reads. |

| bioperl-network | Network package can be used to read and analyze protein-protein interaction networks |

| bioperl-pedigree | Pedigree package has objects for Pedigrees, Individuals, Markers, & Genotypes |

| bioperl-gui | GUI package which for Perl-Tk objects for a Graphical User Interface. Serves as the basis for Genquire |

| bioperl-microarray | Microarray package has preliminary objects for microarray data |

Table 1. BioPerl packages

Release tags and branches

By default, after ‘cloning’ (above), your checkout is on the BioPerl ‘master’ development branch. Git makes it easy to switch to a release tag or branch. For more information on these version control concepts see the repositories and branches section of the Git user’s manual.

To list tags and branches, use:

$ git tag -l

$ git branch -r

To checkout a release tag or branch (for example), use:

$ git checkout bioperl-release-1-6-1 # tag

$ git checkout origin/release-1-6-2 # branch

Keeping up to date

To pull all the latest updates into your local repository, hit:

$ git pull

It is recommended to run this command every time you start to work on code (or if you know there has been a bug fix).

Forking and Pull Requests

The preferred procedure for most developers to contribute changes to BioPerl is to fork the project on GitHub, make changes, and then send a pull request on GitHub to the main BioPerl project describing the changes.

GitHub itself has excellent documentation on forking and pull requests, see:

Developing BioPerl

Checking out with a collaborator account

If you have a GitHub account, have git set up locally on your machine, and been added as a developer or collaborator to our GitHub repository, you can check out the repository and push commits back to it.

% git clone git@github.com:bioperl/bioperl-live.git

The above checks out the master branch of bioperl-live (the core modules) into the ‘bioperl-live’ directory in the current working folder. Similarly, to check out bioperl-db:

% git clone git@github.com:bioperl/bioperl-db.git

Creating a Fork

If you have a GitHub account, you can also create a fork of the repository. This essentially creates a local copy of the repository in your account for you to hack on. The advantage of this is that anyone can fork BioPerl; you do not need direct commit access. The disadvantage: you can’t simply use git pull or variations thereof to update from the repository. This makes sense, as you essentially have created a local copy of the repository in your account with the intent of making your own changes to the code. However, there are ways to work around that (see below)

The main GitHub page of forking repositories gives more specific directions on how to set one up. In general, this is the preferred route of creating and hacking on your own copy of BioPerl, primarily because this doesn’t create a full copy of the repository in your local account (e.g. saves lots of space) and also makes it easier to submit your changes to the core developers to be incorporated into BioPerl.

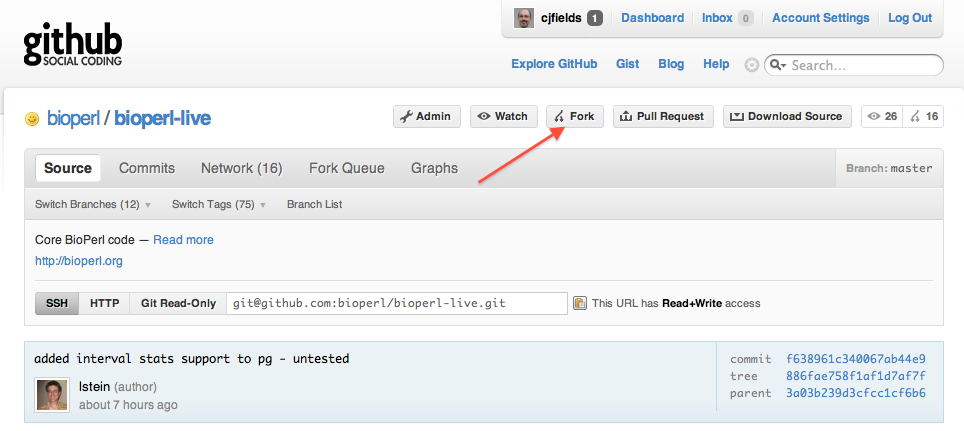

Create a fork of the BioPerl repository

Log in to your account, go to the main BioPerl repository page, and click on the ‘Fork’ button (red arrow above). This will create the fork in your account.

Check out your fork

You will need to clone the repository from your forked code on your account.

From here, you can make changes to the code, make local commits, then push the code back up to GitHub. Note this makes changes only on your fork, not on the main BioPerl repository.

Developing on Branches

With git, everything is a branch, including ‘master’. So, learning to develop on a branch and merge changes over from one branch to another is critical. Luckily, git makes this very easy. See 1.

Making a branch

To create a local branch:

$ git checkout -b my_new_branch

This switches you automatically to that branch:

$ git branch

master

* my_new_branch

Checking out an existing remote branch

For a branch that is not yet in your local repository, makes a new local branch with the same name and sets it up to track the remote branch of the same name.

$ git checkout -t origin/branch_name

One can also checkout a remote branch into a local branch with a different name. The following pulls down the remote branch branch_name into the local branch foo:

$ git checkout --track -b foo origin/branch_name

For a branch that is already in your local repository, just:

$ git checkout branch_name

Making commits to a branch

After you have made some changes to the code (and of course tested the changes by running ./Build test), you will want to commit your changes, and then send the commits to the BioPerl repository. When making commits, try to make each commit self-contained (that is, the commit makes sense and works in and of itself), and write concise, descriptive commit messages. If you have a lot of changes that are unrelated to each other, they should be developed on separate branches.

With git, you make a commit by first this can be done by:

- first staging files with

git add, - making a commit out of them with

git commit.

Since git is a distributed version control system, your commits all occur locally and are not sent anywhere until you push them back to the remote repository with git push. This also means that network connectivity is not required to work and make commits, only for sending with git push.

Basic workflow

Note These are general suggestions for workflows, but they have been demonstrated to work very well in other projects.

- Hack, hack, hack on Foo.pm

git add Foo.pmgit commit -m "Foo system now correctly handles FooBar situation"

You can then follow this up with multiple commits as needed until you are ready to send (push) them to the specific remote repository. If you have a standard master branch checkout from github, you can do this by:

$ git push origin <branch_name>

where branch_name is the name of the branch you are working on.

For convenience, there is also a shorthand form of git commit that stages all working copy changes, and then commits them in one command:

$ git commit -am "Changes to handle FooBar situation"

Be careful with that command, be sure that you know what you are changing. Use git diff and git status.

Resolving conflicts

With git, merges are just a special kind of commit. Usually, the merge is completed and the commit is made automatically. But when there are conflicts that git cannot resolve by itself, it puts your repository in a special state indicating that you are in the middle of resolving a conflicted merge (or rebase, for more advanced users) and drops you back to the command prompt. Usually, conflicts are resolved by editing the conflicted files to fix the conflicts, then adding and committing them with git add and git commit, which completes the merge.

For more on the science of resolving conflicts, see the HOW TO RESOLVE CONFLICTS section in git help merge.

See Resolving a merge in the Git User’s Manual.

Merging changes between branches

Usually, you want to merge changes from some other branch into the local branch you are currently working on. This is done by simply:

$ git merge branch_name

Troubleshooting

Did you get an error? Something like this?

! [rejected] master -> master (non-fast-forward)

error: failed to push some refs to 'git@github.com:bioperl/bioperl-live.git'

To prevent you from losing history, non-fast-forward updates were rejected

Merge the remote changes before pushing again. See the 'Note about

fast-forwards' section of 'git push --help' for details.

Most likely someone else has committed and pushed to the same remote branch in the meantime and now your local copy is out of date. You then have a set of choices, depending on what you want to do.

1a) Try doing

$ git fetch

to bring down any changes that have occurred in the remote repository. Rebase the branch commits to those fetched from the remote repo to replay all your commits over the top of the ones you just pulled down:

$ git rebase origin/master

Of course, you should replace 'origin/master' with whatever remote repo you are using.

1b) You can do all of the above in one set:

$ git pull --rebase origin/master

1c) Or you can simply merge the commits to your local branch:

$ git pull

The last version, though less verbose, is also a bit dirtier in that you see a merge message as well as replay the commit messages.

2) To catch everything up

$ git push

Sending a new branch to GitHub

$ git push origin my_funky_branch

will send the local ‘my_funky_branch’ to the repository on GitHub.

Deleting a remote branch

To delete the remote branch ‘branch_to_delete’, you push * (nothing) with it as the push target.

git push origin :branch_to_delete

Backing out prior commits

To revert the prior commit on the branch you are on:

git revert HEAD

To revert a specific commit, where the commit has <SHA>:

git revert <SHA>

More elaborate reversions are also allowed (look under ‘Specifying Revisions’).

How BioPerl’s GitHub repository is configured

Archived Branches

At the time of BioPerl’s conversion to Git (May 2010), branches in Subversion dating from 2007 or before were archived in refs/archives/.These branches are not visible in the normal workflow. To list them:

$ git ls-remote origin refs/archives/*

To inspect one of them:

$ git fetch origin refs/archives/branches/branch_to_inspect

$ git log FETCH_HEAD

$ git show FETCH_HEAD

# and so on using the FETCH_HEAD as a convenient temporary handle on the branch

To move one of them into the current set of branches:

$ git fetch origin refs/archives/heads/branch_to_resurrect

$ git push origin FETCH_HEAD:refs/heads/new_name_for_this_branch :refs/archives/heads/branch_to_resurrect

The Fork Queue

On Github, BioPerl collaborators will see a “Fork Queue”. For example, here is the bioperl-live fork queue.

Note that commits from anyone’s fork of a BioPerl repository will appear there and may not be ready to be committed to master (details here).

Submitting a Pull Request

One can (when chosen, hopefully after testing) submit a ‘pull request’ from GitHub. GitHub has some very good instructions for doing so.

For the BioPerl project, we suggest NOT sending a pull request notice to all the collaborators for the project, just to the user bioperl. This will send a notice to the main developer list indicating that a pull request has been submitted; otherwise, every collaborator will end up getting two copies of pull requests. This is an issue that is being fixed by the GitHub developers.

Processing a Pull Request

For minor additions such as documentation fixes and small bug fixes, a developer who is a collaborator can use the fork queue to merge in the forked code.

For all other changes, after a decent code review (does it break the API? do all tests still pass?), one can do the following. From the command line:

- Add the forked repository as a new remote:

git remote add <fork_name> git://github.com/<github_user>/bioperl-live.git

From this point on, there are two ways you can merge in commits. The first method is considered cleaner (nothing goes to the ‘master’ branch until tests pass) and is preferred.

Fetch/Rebase/Merge/Push

1) Fetch the remote changes:

git fetch <fork_name>

2) Create a local branch based on the remote one:

git checkout -b merge-fork <fork_name> /master

3) Run tests on the new branch to make sure everything passes. Don’t forget to add any necessary changes to the ‘Changes’ file, and commit that:

# edit Changes

git add Changes

git commit -m 'update Changes'

4) Rebase against the local master branch (MAKE SURE THIS IS CLEAN):

git rebase master

5) Checkout master branch:

git checkout master

6) Merge changes from the fork branch and push upstream (the -s is recommended, it indicates who signed off on the commit):

git merge merge-fork

git push origin master

Pull/Push

This second version simply merges changes in, akin to a SVN-like ‘merge’. With git, however, this is considered a bit ‘dirtier’ for a couple of reasons:

- First, you are merging changes directly into the master branch from the remote fork, so you may have to revert if said changes don’t pass tests. You can work around this by creating a new branch from your local ‘master’ branch and merging in that.

- Second, merges without a prior rebase from the fork branch may repeat the commits made on the local branch, which clutters the commit history.

With both reasons above one could work around them (create a branch from ‘master’ and merge into that, or use a rebase), but if you are considering this you might as well use the cleaner version above.

1) Change to the branch you wish to merge into (here, the ‘master’ branch):

git checkout master

2) Merge from the proper remote branch to the one you are currently on, adding a commit message:

git merge <fork_name>/master

Note If you are worried about the changes and don’t want to commit them in right away, you can add a --no-commit flag:

git merge --no-commit <local name for fork>/master

3) Test the changes:

perl Build.PL

./Build

./Build test

Don’t forget to add any necessary changes to the ‘Changes’ file, and commit that:

# edit Changes

git add Changes

git commit -m 'update Changes'

4) Push merged changes and additional commits back to origin:

git push origin master

A few standard development workflows

Documentation fixes

If there are some small documentation glitches that can be fixed very quickly, one can make these locally on the ‘master’ branch and commit them in.

$ git checkout master

$ git pull

# ...add doc fixes...

$ git add Foo.pm

$ git commit -m 'misspelling'

$ git push

Larger scale doc fixes (such as global changes to fix POD errors) should be done on a branch (see below).

Bug fixes

Bug fixes should be done on a ‘topic’ branch. These can be labeled however you want, but it’s generally a good idea to reference any bug report (if there is one).

$ git checkout -b topic/bug_1234

...patch patch patch...

...intermittent commits to the branch on remote...

$ git push origin topic/bug_1234

...test commit test commit...

...merge fixes...

$ git checkout master

$ git merge topic/bug_1234

$ git push origin master

After testing by others, this branch can be safely deleted locally using git branch -d (which only deletes if the code has been merged):

$ git branch -d topic/bug_1234

Don’t forget to delete the remote branch as well.

$ git push origin :topic/bug_1234

New or modified features

These would follow the same pattern as a bug fix, with the exception that the branch name would be something short and descriptive about the work being done.

For instance, recent Bio::FeatureIO work was:

$ git checkout -b topic/featureio_refactor

The rest would follow a similar pattern to the above. One critical piece would be, if development on the branch is expected to take a while, to ensure you are routinely syncing your feature branch with the master branch:

...on your branch...

$ git merge master

Release branches

To list branches, do:

git branch -r

To checkout a release branch, do (for example):

git checkout origin/release-1-6-2